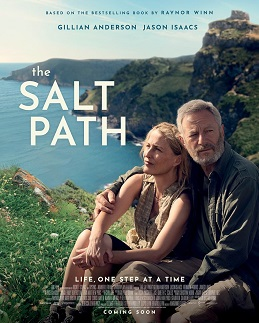

On the last evening of May 2025, I was immersed in The Salt Path, the new film adaptation of Raynor Winn’s memoir. Having read the book some years ago, listened to it on the radio, and walked parts of the South West Coast Path with my son at various ages, I wasn’t sure how the cinematic version would handle such precarious, deeply personal material. It could easily have slipped into sentimentalism or tourist-board gloss. But it didn’t.

What unfolded instead was a visceral, immersive experience—lush, cinematic, rain-soaked and windswept, and strikingly alive to the real salt of life: grief, love, pain, place, and presence. These are five lessons I came away with, steeped in salt and path, in walking and being:

1. Salt is in the body, the tears, the sea—and the healing

The film captures the visceral saltiness of life—not just the sea spray and the cracked skin, but the sting of hardship and the sharp tang of humour that sees them through. Moth and Raynor—not Ray—are drenched by waves crashing through their tent, scorched by sun, chilled by gales. Their skin is weathered and salted by experience. We feel the damp sleeping bags, the sting of blisters, the ache of exclusion, the bitter aftertaste of being cast out. But salt is never only suffering. It is also medicine. It preserves, it draws out pain, it binds.

As Raynor Winn writes in The Salt Path:

“Salt was in the air, in my hair, in my sleeping bag, in the porridge, in our boots… We were becoming part of the landscape, slowly salted ourselves.”

(Winn, 2018, p. 62)

That act of slow salting becomes transformation. Through deprivation, they are seasoned—both physically and spiritually. It’s not just the elements they weather, but the looming shadow of Moth’s illness. Diagnosed with corticobasal degeneration (CBD), a rare and terminal neurodegenerative disease with symptoms similar to PSP (progressive supranuclear palsy), Moth was advised to rest, to avoid exertion, and to prepare for the worst. But instead, he walked. Against all medical expectations, he grew stronger. As Raynor later reflected, “I watched him re-build himself… he became more well with every step” (PSP Association, 2023).

In the film, Moth’s humour is as bracing as the wind, as salty as the sea. Even in despair, he reaches for laughter—not to dismiss pain, but to hold it more lightly. At one low point, weakened and discouraged, he jokes that Raynor should take him back to the shop and get a new one. The remark is laced with self-mockery and heartbreak, a man confronting his own perceived uselessness with wit. But Raynor, without hesitation, replies: “Never.” The moment is piercing. It is love in its most elemental form—steadfast, unadorned, absolute.

This is the kind of salt that seasons the whole journey. Not just the spray in their hair or the crust on their clothes, but the emotional grit that binds them. Humour becomes survival. Their shared laughter is a form of resistance, a way of reclaiming agency in the face of illness, poverty, and social abandonment. Moth’s salty humour doesn’t dilute the suffering—it flavours it, offering sharpness, contrast, and the surprising possibility of joy.

The salted blackberries glinting in the mist become more than a forager’s prize—they are a fleeting beauty, the kind that nourishes not only the body but the soul. Salt as metaphor moves from discomfort to cure: it stings, yes, but it also cleanses. It sharpens the senses. It keeps things alive.

2. Walking is a form of becoming

To walk such a path—day after day, in sun and in storm—is to be transformed. What begins as shock, hiding from bailiffs, clutching a guidebook like a raft, becomes something else: a kind of pilgrimage. A shedding. A remembering. You see Moth and Raynor become part of the landscape, their bodies broken down and remade by the terrain.

In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari describe becoming not as imitation or transition to a fixed state, but as “a verb with a consistency all its own” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 239). Moth and Raynor do not become like the land; they enter into a movement with it—a becoming-landscape, a becoming-weathered, a becoming-wild.

I remember carrying my son on my back from St Ives to Zennor, and doing it again years later as he walked beside me. The path changes you—and changes with you. Each step, a becoming. Each storm, a call to shed something false and emerge slightly more true.

3. The landscape is not background—it is the story

One of the film’s greatest achievements is how it refuses to reduce the path to a scenic backdrop. The names of towns and landmarks are incidental. What matters is the wind lashing your face, the shingle slipping underfoot, the crack of a stick, the warmth of a pub fire after hours in the cold. This is not a postcard journey. It is the slow, real-time geography of presence.

The tradition of seeing nature not as “other” but as divine—as co-extensive with being—runs through both philosophy and poetry. For Spinoza, “God is the immanent, not the transitive, cause of all things” (Spinoza, 2000, p. 14, Part I, Prop. XVIII), meaning that nature is God, not something created and separate. This worldview suffuses The Salt Path: the film, like the book, evokes the landscape not as something to dominate or display, but something to become part of.

The tradition continues in Romantic poetry. Wordsworth, walking the Lakeland fells over two centuries ago, wrote of nature as “the anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse / The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul / Of all my moral being” (Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, 1798).

Like Moth reciting Beowulf under the stars, the Winns find in the land not a setting, but a mythic ground of being. The weather, the terrain, the animals, the moments of silence and hardship—these are not background detail but the story itself.

4. Homelessness is not just a policy issue—it’s a wound

The Salt Path is a love story, yes—but also a social story. The Winns lose everything. The trauma of eviction, the moment of hiding in the bathroom from the bailiffs, is still with me from the book. The film honours their story without romanticising it. The humiliation of being mistaken for someone of “status” and then dropped once their reality is revealed—it’s as cutting as any storm. There is tenderness too: from strangers, from a woman in a pub, from those who choose to see the Winns’ dignity rather than their destitution. But the system that failed them haunts the path.

Recent academic discourse underscores the systemic nature of homelessness. For instance, Nichols, Cullingham, and Malenfant (2024) argue that state-driven interventions, even those framed as preventive public health measures, can inadvertently exacerbate structural inequalities, highlighting the ethical and political dimensions of homelessness.

5. Home is not a house—it’s a way of being

Beginning: HWÆT. WE GARDE / na in geardagum, þeodcyninga / þrym gefrunon… (translation: How much we of Spear-Da/nes, in days gone by, of kings / the glory have heard…)

At its core, The Salt Path is about love. Not a tidy love, but one honed by adversity. Moth’s humour (beautifully rendered by Jason Isaacs), Raynor’s quiet endurance, their wordless intimacy—they discover home in each other, and in the act of walking. The film, like the book, is an invitation to live differently: to walk more slowly, notice more deeply, feel more vividly. It’s about being kind—to yourself, to others, to the path beneath your feet.

Moth’s talisman throughout is Beowulf—an epic that begins not in battle, but with a funeral:

“Lo! the Spear-Danes’ glory through splendid achievements / The folk-kings’ former fame we have heard of” (Beowulf, lines 1–2).

It’s a story of exile and return, of monstrous trials and human endurance. At one point in the film, Moth’s recitation of the poem becomes a kind of magic, reviving their dignity in the eyes of others, anchoring him not as a vagrant but as a bard—a knower of stories, a bearer of meaning.

Simon Armitage, who has translated Beowulf twice (2006; 2020), describes it as “an ancestor of our literature, our language, and perhaps even our understanding of what it means to travel, fight, lose, and come home” (Armitage, 2020). The poem becomes the mythic core of Moth’s understanding of life. Through its cadences, he remembers that home isn’t a roof or a mortgage—it’s a mode of being in the world, one forged through adversity, loyalty, and words shared by the fire.

As I left the Finsbury Park Picturehouse, I felt like I’d walked part of the coast again. I remembered those salty treks with my son—him on my back, then beside me, then striding ahead. Each step a letting go, and a return. Each footfall a quiet reminder that we make and remake home not in bricks and mortar, but in memory, movement, and mutual care.

Final Thought: The Path Is Still There

Whether you’re carrying a child or a grief, whether you’re lost or found, the path doesn’t judge. It waits. And as The Salt Path shows so beautifully, sometimes the only way home is to walk it.

References

Armitage, S. (2006) Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Faber & Faber.

Armitage, S. (2020) The Death of King Arthur & Beowulf: A Dual Translation. London: W.W. Norton.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Heaney, S. (1999) Beowulf: A New Translation. London: Faber & Faber.

Nichols, N., Cullingham, S. and Malenfant, J. (2024) ‘The Politics of Prevention and Government Responses to Homelessness’, International Journal on Homelessness, 4(1), pp. 171–184.

PSP Association (2023) Raynor and Moth’s Story. Available at: https://www.pspassociation.org.uk/information-and-support/living-with-psp-cbd/personal-experiences/raynor-and-moths-story/ (Accessed: 1 June 2025).

Spinoza, B. (2000) Ethics. Translated by G.H.R. Parkinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Winn, R. (2018) The Salt Path. London: Penguin Books.

Wordsworth, W. (1798) ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’, in Lyrical Ballads. London: J. & A. Arch.

Leave a Reply