Patrick White is often hailed as Australia’s greatest novelist – the only Australian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (1973) – yet his cultural status can be paradoxical. Despite international fame, he has sometimes been seen as distant or “difficult,” even in his home country. In 2023, literary scholar Reuben Mackey reflected on White’s legacy 50 years after the Nobel win, noting that “Ever since he won the Nobel prize, White has been unable to escape the institutional framing of his work” (Mackey 2023). In other words, White’s novels are frequently boxed into a pedestal of prestige – admired, yes, but perhaps not read as intimately as they deserve. Mackey’s article lamented that the anniversary of White’s Nobel went largely unnoticed, prompting questions about whether contemporary readers still connect with White’s fiction. This lack of current discourse around White’s work belies the profound lessons woven through his novels.

My relationship with Patrick White’s work

On a personal note, I first encountered Patrick White’s writing as a university student, and the experience was challenging yet revelatory. I read his long novel about a disturbed Australian artist, The Vivisector, not because it was a prescribed text on my English Literature degree, but because it offered a refreshing release from much of the reading I had to do. I fell in love with White’s luminous prose, evocative scene setting and complex characters. The Vivisector – a 1970 novel about an artist’s ruthless quest for truth – left me shaken and inspired in equal measure. I still recall long weekend afternoons, immersed in White’s pages and marveling at how he could capture not only the inner spiritual yearnings of a flawed human being but also paint a picture of an entire nation, its people and extraordinary landscapes. I felt as though I was living and creating art in the Australian outback, experiencing a complete and extraordinary life. Reading White feels like ‘human experience’ because his prose sucks you in to an entire world. That initial immersion led me to explore White’s other novels like Voss and Riders in the Chariot, each reading deepening my appreciation for his craft and ideas. White quickly went from an intimidating Nobel Laureate I “had to” study, to a beloved mentor in literary form. His works felt alive to me – teeming with insight into life’s big questions – and surprisingly relevant. In reflecting on Patrick White’s legacy now, I realize how much his novels have taught me not just about literature, but about living. Here are four key insights from White’s fiction that continue to resonate, offered in an accessible way for readers new to his work.

1. Mindfulness and the Beauty of the Present Moment

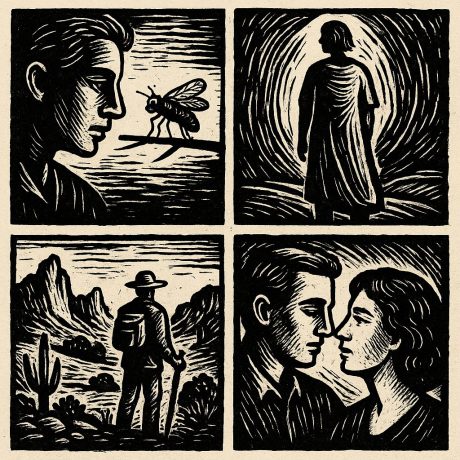

One striking quality of Patrick White’s writing is his almost mystical attention to the present moment – the way he illuminates fleeting details and everyday beauty. Long before “mindfulness” became a buzzword, White’s characters were pausing to notice transcendence in the mundane. His prose often zooms in on small, transient phenomena and reveals in them a kind of hidden glory. For example, in the outback epic Voss (1957), a gentle missionary named Palfreyman suddenly stops to marvel at a tiny insect amid the Australian wilderness: “‘Look,’ said Palfreyman, pointing at a species of diaphanous fly that had alighted on the rail of the bridge. It appeared that he was fascinated by the insect, glittering in its life with all the colours of decomposition…” (White 1957: 47). In this moment, Palfreyman is so absorbed in the iridescent fly that he barely hears his companion Voss speaking. The novel suggests that to truly see this fragile living jewel – “glittering in its life” – is a kind of spiritual act, an awakening. White’s fiction is full of such instances where an ostensibly trivial detail becomes a gateway to insight or epiphany. Literary critic Michael Wilding observes that White’s art often hinges on “moments of epiphany: sudden flashes of seeing … The seemingly trivial produces the stimulus.” (Wilding 1991: 165). In other words, a minor detail in White’s narrative – an insect, a stray remark, a pattern of light and shadow – can trigger a character’s leap of perception or feeling. Through these moments, White teaches us the value of mindfulness: the idea that the present, if attended to, brims with beauty and meaning.

White’s descriptive passages encourage readers to slow down and notice the “little” things. His style, while complex, often works by accumulation of impressionistic detail rather than straightforward realism. As Wilding notes, White writes “by impression rather than detail,” using external scenes as “an accompaniment to states of mind” (Wilding 1991: 167). In Riders in the Chariot (1961), for instance, an Australian suburban landscape is described not for factual precision but for its psychological resonance: “The rather scrubby, indigenous trees [were] not so much of interest to the eye as an accompaniment to states of mind…” (White 1961, quoted in Wilding 1991). Here White suggests that the scenery’s value lies in how it feels to the observer – how it mirrors inner experience. By tying the physical environment to his characters’ mental and spiritual states, White effectively grounds the abstract in the concrete here-and-now. Reading his novels, we are invited to contemplate alongside his characters: to see eternity in a moment, or profundity in a “scrubby” tree or a fly on a bridge railing. This lesson in mindfulness – finding the miraculous in the present moment – is a gift White consistently offers his readers. In a fast-paced world, his novels gently insist that we pause, look, and listen, because meaning is all around us if only we attend.

2. Questioning Gender and Embracing Fluid Identity

Another remarkably forward-thinking aspect of Patrick White’s work is his interrogation of gender and identity, most notably in his novel The Twyborn Affair (1979). Decades before terms like “gender fluidity” were common, White crafted a story centred on a character who lives as both male and female at different stages of life. The Twyborn Affair follows the life of Eddie Twyborn – born male – who in three parts of the novel inhabits three personas: a woman named Eudoxia on the French Riviera before WWI, a man named Eddie living in the Australian outback after the war, and finally a middle-aged woman, Eadith, running a brothel in London on the eve of WWII. Each incarnation is the “same” person, and yet not quite, as Eddie/Eudoxia/Eadith continuously negotiates the confines of gendered expectations. By structurally changing the protagonist’s name and gender presentation in each section, White challenges the reader to reconsider the stability of identity. Who is “the real” Twyborn – the woman, the man, or something in-between? White refuses to give a simple answer. Instead, he portrays identity as something multifaceted and fluid, composed of many selves.

What’s astonishing is how sensitively White handles these themes in 1979, anticipating contemporary conversations about transgender and non-binary identities. The Twyborn Affair was controversial in its day, but now feels prescient. Literary scholars have noted that the novel “critiques heterosexualities and cisgendered binaries that restrict the fluidity of both desire and bodily autonomy.” (Rowen 2018). In other words, White is actively deconstructing the strict male/female binary; his protagonist defies the notion that one must be either/or. Throughout the novel, Eddie/Twyborn is searching for an authentic self, painfully aware that society’s labels never quite fit. At one point, in a moment of anguished clarity, the protagonist even declares: “I am no longer a fiction but a real human being.” This powerful statement (which gives a recent critical essay its title) signals Twyborn’s yearning to be seen for their true self, beyond imposed categories. White interrogates gender not as an abstract issue but through the visceral reality of his character’s life – including intimate relationships that cross conventional lines. For instance, in Part I Eddie (as Eudoxia) lives as the “wife” of an older male aristocrat, while in Part II (as Eddie, a man) he attracts both a female lover and unwanted male attention. Such plot elements boldly question how gender roles and sexuality are policed.

White’s treatment of these themes was ahead of its time, and it carries a humanistic message that feels strikingly relevant now: gender can be complex, and compassion is needed for those whose identity doesn’t fit neat labels. By the novel’s end, Eddie’s own mother unwittingly meets him in his female persona (Eadith) – a charged encounter that underscores how identity can both conceal and reveal. We as readers come to empathize with Twyborn’s fragmentation and courage. In embracing this character’s journey, Patrick White teaches us to interrogate gender norms and to recognize the multifaceted nature of identity. His novels invite us to see people for who they are – in all their elusive, in-between truth – rather than force them into preconceived boxes. This lesson in empathy and open-mindedness around gender makes The Twyborn Affair feel incredibly modern, a testament to White’s nuanced understanding of human nature.

3. Decolonising Thought: Challenging Eurocentric Narratives

Patrick White was also a pioneer in decolonising literature – using Australian settings and perspectives to push back against Eurocentric narratives. Writing in the mid-20th century, White helped put Australia on the literary map in a profound way. The Swedish Academy, in awarding him the Nobel Prize, praised his work as “an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature” (Nobel Prize Committee 1973, as cited in Woollard 2024). This “new continent” was not just a geographic reference but a metaphor for bringing Australian landscapes, voices, and stories – long marginalised – into the center of literary conversation. Prior to White, Australian fiction was often seen as provincial or secondary to European literature. White shattered that notion by writing novels of grand vision (Voss, The Tree of Man, Riders in the Chariot, etc.) set unmistakably in Australian soil yet grappling with universal themes. His success and international recognition challenged the lingering colonial attitude that serious culture only came from Europe or England.

In his novels, White deliberately subverts Eurocentric tropes. Take Voss, for example. On one level, it’s a colonial-era tale of an explorer (loosely inspired by Ludwig Leichhardt) embarking on an expedition to cross the Australian continent. A conventional colonial narrative might celebrate the European hero’s conquest of the unknown land. White’s Voss does something very different: it transforms the journey into a spiritual and existential quest, and it pointedly includes perspectives that undermine the colonial enterprise. Indigenous Australian characters appear at the margins of Voss, not romanticized but shown in fleeting, intriguing glimpses that suggest an entirely different relationship to the land. In one scene, an Aboriginal group comes across the explorers’ campsite and finds a sack of white flour – a European staple. They tear it open, and one Aboriginal man ends up covered in the flour, literally turned white and ghostly. This vivid image is laden with symbolism: the “crumbly promise of Western colonialism” disintegrates, leaving only a mess. As one critic notes, the episode satirically portrays the futility of the colonizers’ efforts – the land gives them nothing sustaining, only white powder (Sutar 2024: 122). The colonial quest in Voss is thus exposed as an arrogant delusion; the true mysteries of the continent elude Voss and ultimately destroy him. White, writing in the 1950s, was subtly dismantling the myth of heroic exploration and exposing its hubris.

Riders in the Chariot provides another powerful example of White’s decolonising approach. This 1961 novel gathers four outsider figures in an Australian suburb – among them an Aboriginal painter (Alf Dubbo) and a Jewish refugee from Europe (Mordecai Himmelfarb). By foregrounding an Indigenous Australian and a Jewish Holocaust survivor as two of the novel’s spiritual visionaries, White upends the Eurocentric, Christian-dominated lens through which Australian society often viewed itself. He invites us into the inner lives of those at the margins: Alf paints mystical visions derived from Aboriginal tradition and Christian symbolism, while Himmelfarb, a gentle scholar, endures anti-Semitic persecution in Australia reminiscent of the terrors he escaped in Europe. Notably, White pointedly critiques Australia’s vaunted ideal of mateship (comradeship among white Aussie men) by showing how these outsiders are excluded from it. In one scene, a well-meaning Aussie worker asks Himmelfarb, “Never got yerself a mate?” When Himmelfarb softly replies, “Anybody is my mate… I shall take Providence as my mate,” the response bewilders and alienates his questioner (White 1961: 307). This quietly tragic exchange highlights a clash of worldviews: Himmelfarb’s cosmopolitan, spiritual perspective versus the narrow local norm. As scholar Michael Wilding explains, Riders in the Chariot “explicitly rejects mateship”, displacing that old Australian tradition with a new vision of community that transcends race and creed. The novel implies that true fellowship might be found not in one’s “own kind” alone, but in a broader humanity united by compassion and suffering.

Through such narrative choices, Patrick White was effectively decolonising Australian literature – telling stories from the standpoint of the colonised and the outsider, not just the colonial “self.” He challenged the Eurocentric assumption that only European experiences were universal; instead, he showed that an Australian outback journey (Voss), or the inner life of an Aboriginal artist (Alf Dubbo), or the trauma of a Jewish migrant, all contained profound human truths worthy of epic treatment. White’s example teaches us to question inherited imperial narratives and to listen to voices from the periphery. In doing so, he helped Australian writers (and readers) see their own landscape and culture as rich sources of meaning, not merely as shadows of England or Europe. The lesson here is one of cultural self-realization: our own backyard, however “provincial” it might seem to others, holds stories and perspectives that can speak to the world. Patrick White’s novels, by interweaving the local and the universal, invite us to broaden the literary canon and our minds beyond Eurocentric boundaries.

4. Authentic Relationships in All Their Complexity

Finally, Patrick White’s novels are masterful in their portrayal of human relationships – not idealised romances or simplistic friendships, but real, messy, complex bonds between people. In White’s fictional worlds, love and connection are often difficult to attain and fraught with misunderstanding, yet they are rendered with a psychological authenticity that is both compelling and moving. Many of his stories centre on characters who struggle to bridge the gap between selves, yearning for connection but often thwarted by ego, pride, or social barriers. Through these nuanced depictions, White teaches us about the challenges and the profound importance of authentic relationships.

Take The Vivisector, the novel that I first read as a student. Its protagonist, Hurtle Duffield, is an egocentric painter who essentially “vivisects” the people in his life – using their love and suffering as material for his art. Hurtle’s relationships are complex and often painful. For instance, he has a long relationship with Nance, a kind-hearted prostitute who genuinely loves him, yet he remains emotionally distant, observing her suffering almost clinically as inspiration. He is later drawn to a young musical prodigy, in a bond that is part mentorship, part obsessive fascination, and morally ambiguous. Hurtle can’t fully reciprocate love because he is consumed by his artistic vision. And yet, White doesn’t paint him as a monster; rather, we see Hurtle’s own neediness and fear of vulnerability under his aloof exterior. The relationships in The Vivisector are tangled, asymmetrical, and utterly human – there are betrayals and devotion, exploitation and tenderness all intertwined. At one point Hurtle reflects (in his brusque way) on the nature of love, asking: “There are different ways of loving, aren’t there?” (White 1970). This rhetorical question cuts to the heart of White’s view on relationships: love is not one-size-fits-all, and it often comes laden with flaws. In The Vivisector and beyond, White shows that love can be mingled with selfishness or cruelty, yet it remains a driving force for his characters, capable of moments of redemption and grace.

Crucially, White’s portrayals of relationships are never trivial or merely sentimental. Even the bonds that might conventionally be seen as positive are handled with depth. In Voss, the intense spiritual connection between the explorer Voss and young Laura is conducted mostly through letters and psychic communion – an extraordinary relationship that defies physical distance and even logic. It’s not a typical romance at all; they barely meet, and yet their bond sustains Voss on his doomed journey. White uses this unusual connection to explore how two solitary souls might truly understand each other beyond words – and also how easily they can still misread one another. In Riders in the Chariot, the unlikely friendship of the four outsiders (mentioned earlier) is poignant precisely because it’s so tentative and wordless – they recognize a shared vision or “light” in each other, but society’s brutality intervenes before that fellowship can fully flourish. Such moments in White’s work underscore that genuine communion between people is rare and precious. His characters often fail to connect, or connect only fleetingly, but those instances are depicted with a kind of sacred awe.

White’s insight, then, is that authentic relationships are hard-won and often imperfect, yet they are central to the human experience. Even characters who are “loners” in his novels carry an undercurrent of longing for understanding. Literary reviewers have praised White’s almost unparalleled ability to capture this aspect of life. As one critic noted, White excels at portraying “the difficulty of communication and relationships between the characters”, conveying how people struggle to articulate feelings and bridge their isolation. That difficulty is something we all know in life, and seeing it reflected so honestly on the page can be bracing but also comforting. White doesn’t give us storybook happy endings; instead, he offers something truer – a mirror of our own relational triumphs and failures. Through reading his work, we come to appreciate that real love or friendship is not a constant blissful state but an evolving negotiation, an achievement of empathy amid friction. It’s notable that even in his novel, The Eye of the Storm (1973), White focused on a domineering elderly mother and her alienated adult children, peeling back the layers of resentment, guilt, and enduring affection that tie families together. He fearlessly exposes the “inhuman” streak in human beings (as one of his oft-cited lines goes, “There’s nothing so inhuman as a human being”), yet he also reveals the moments of grace when people transcend their inhumanity through compassion or sacrifice. The enduring lesson from White’s narratives is that authentic relationships – however difficult and complex – are the crucibles in which we discover our humanity. In confronting the uncomfortable truths of how we treat those we love, White ultimately leads us toward a more honest and profound understanding of love itself.

Concluding Thoughts

From mindfulness in the moment, to gender fluidity, to postcolonial perspectives, to the intricacies of love – the novels of Patrick White are a rich repository of wisdom on the human condition. Reading White requires patience and willingness to engage with ambiguity, but the reward is a deeply affecting and enlightening experience. In my own journey, Patrick White’s books have been companions in exploring questions of spirituality, identity, culture, and connection. They do what the best literature should: challenge us, move us, and expand our empathy. To conclude this reflection, I offer a small creative tribute – a short poem I wrote inspired by White’s motifs of mortality, authenticity, the soul’s quest, and sudden aesthetic revelation. It’s an attempt to capture, in a lyrical way, the kind of insight one might glean from stepping into a Patrick White novel.

A candle breathes; the room answers.

Wax warms; timber releases a resin note;

dust turns in a slow swim of light.

Attention is a muscle; it wakes.

Palfreyman on the bridge in Voss

leans closer to the fly, a pulse of colour on a rail,

river smell in his throat, sun hot on the neck.

Laura reads the weather off paper and skin,

ink drying under her hand, a kettle ticking,

silence not absence but a field alive with signals.

Alf Dubbo in Riders in the Chariot

works linseed and pigment into board;

gum leaves click beyond the window;

paint skins over; the room fills with breath and colour.

Mordecai Himmelfarb rides the tram,

metallic sway in his knees, the taste of bread,

a book warm from his pocket,

a holiness that smells of sweat and rain.

Hurtle Duffield in The Vivisector

scrapes a brush dry, turpentine stinging the nose;

canvas grates under his knuckles;

Nance sets down a cup, steam on his cheek,

ordinary kindness anchoring the room.

Art opens the body of love;

it hurts; it clarifies.

Eddie Twyborn moves through rooms and weather,

Eudoxia’s silk rasping the wrist,

Eddie’s boots carrying heat from the dust,

Eadith’s mirror cool as water on the face;

the self is not a fixed shape but a current,

felt in fabric, in footfall, in breath.

The country keeps teaching.

Flour bursts white in Voss and coats a body like chalk;

the mouth dries; the wind will not be owned.

Scrubby trees in Riders do not adorn the eye;

they keep time with the mind,

leaves clicking like beads on a string of thought.

What does White ask of us; to come back to the body.

To live by touch and scent and sound,

to let the small thing call us to order,

the fly’s wing, the tram’s sway, the kitchen’s steam,

the paint’s slow skin, the scratch of a pen,

the weight of a hand taken and a hand returned.

Mindfulness here is not a pose,

it is staying with what is present,

even when it stings, even when it shines.

Decolonising begins where the map blurs on the tongue,

where flour tastes of chalk and loss,

where other stories speak and we listen with the skin.

Love is work; identity is weather;

country is a teacher that withholds and gives.

We travel with them, Voss through sand, Laura through silence,

Alf through colour, Himmelfarb through scorn,

Hurtle through canvases, Nance through patience,

Eudoxia, Eddie, Eadith through the plural body,

each life an instruction in how to sense the world back.

The candle gutters, steadies.

We keep looking until looking becomes touch,

keep listening until the room answers,

keep breathing until the air carries meaning.

This is how we live again,

inside the difficult light.

References and links

ANZ LitLovers. 2014. Riders in the Chariot (1961), by Patrick White. Available at: https://anzlitlovers.com/2014/05/04/riders-in-the-chariot-1961-by-patrick-white/ (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Complete Review. n.d. Patrick White at the Complete Review. Available at: https://www.complete-review.com/authors/whitep.htm (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Complete Review. n.d. Voss – Patrick White (review). Available at: https://www.complete-review.com/reviews/whitep/voss.htm (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Complete Review. n.d. Riders in the Chariot – Patrick White (review). Available at: https://www.complete-review.com/reviews/whitep/riders.htm (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Complete Review. n.d. The Vivisector – Patrick White (review). Available at: https://www.complete-review.com/reviews/whitep/vivisect.htm (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Complete Review. 2023. ‘(Not?) reading Patrick White’ — blog note referencing Reuben Mackey. the complete review: Literary Saloon, 5 Oct. Available at: https://www.complete-review.com/saloon/archive/202310a.htm (Accessed 27 September 2025).

JSTOR Daily (Woollard, C.M.). 2024. The Two Worlds of Patrick White. 4 Dec. Available at: https://daily.jstor.org/the-two-worlds-of-patrick-white/ (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Mackey, R. (2023) Patrick White was the first Australian writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature – 50 years later, is he still being read? (republished). Yahoo News Australia, 4 Oct. Available at: https://au.news.yahoo.com/patrick-white-first-australian-writer-190524187.html (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Mackey, R. (2023). Patrick White was the first Australian writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature – 50 years later, is he still being read? (syndication). Tolerance.ca, 4 Oct. Available at: https://www.tolerance.ca/ArticleExt.aspx?ID=540989&L=en (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Nobel Prize. (1973). Press release: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1973 — Patrick White. Available at: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1973/press-release/ (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Nobel Prize. (2001). Patrick White – Existential explorer. Available at: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1973/white/article/ (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Persee (Wilding, M.). 1991. ‘Patrick White: The Politics of Modernism.’ RANAM, 24, pp. 163–171. Available at: https://www.persee.fr/doc/ranam_0557-6989_1991_num_24_1_1244 (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Rowen, D. 2018. ‘“I am no longer a fiction but a real human being”: The Modernist Queer Body in Patrick White’s The Twyborn Affair (1979).’ Hecate, 44(1–2), pp. 59–75. Abstract via Gale Literature Resource Center: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA610843758&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&p=LitRC (Accessed 27 September 2025). Journal info: https://hecate.communications-arts.uq.edu.au/about

Sutar, S. 2024. ‘Postcolonial Evaluation of Patrick White’s Selected Fictions.’ International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 3(5), pp. 117–123. Available at: https://academicjournal.ijraw.com/media/post/IJRAW-3-5-27.1.pdf (Accessed 27 September 2025).

University of Cape Town (Callaghan, M.). 1987. Immanence and Transcendence in Patrick White (MA thesis). Quotation on Palfreyman; Voss, p. 47. Available at: https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/11427/23180/1/Callaghan_Immanencetranscendence_1987.pdf (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Van Niekerk, T. (2002). ‘Of The Tree of Man and Voss.’ CORE (paper PDF). Contains the Palfreyman “diaphanous fly” citation (Voss, p. 47). Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/145055163.pdf (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Wikipedia. (2025) (latest rev.). The Twyborn Affair. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Twyborn_Affair (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Wikipedia. (2025) (latest rev.). Patrick White. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_White (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Quotations cited (web corroboration)

Goodreads. n.d. ‘There’s nothing so inhuman as a human being.’ The Vivisector. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/838696-there-s-nothing-so-inhuman-as-a-human-being (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Goodreads. n.d. The Vivisector — quotes. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/2412036-the-vivisector (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Tumblr. 2019. ‘There are different ways of loving, aren’t there?’ The Vivisector. Available at: https://octoberthoughts.tumblr.com/post/186275289433/quotefeeling-there-are-different-ways-of (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Additional critical/context links used in the blog

Academia.edu (Wilding, M.). n.d. Patrick White: The Politics of Modernism (alt. copy). Available at: https://www.academia.edu/41278476/Patrick_White_The_Politics_of_Modernism (Accessed 27 September 2025).

ARIEL (Williams, M.H.). 2009. ‘The Evolution of Artistic Faith in Patrick White’s Riders in the Chariot.’ ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 40(3), pp. 45–70. PDF: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ariel/article/download/34917/28927 (Accessed 27 September 2025).

ANU Open Research (Steven, L.). 1983. Dissociation and Wholeness in Patrick White’s Fiction (PhD). Available at: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/14178/1/fulltext.pdf (Accessed 27 September 2025).

Leave a Reply