Lessons from a Joyful Workshop with Danish Students at Goldsmiths

When a group of enthusiastic Danish teenagers arrived at Goldsmiths for a creative writing workshop, led by their teacher, the brilliant Margit from the Danish Association of Teachers of English (DATE) and the UK’s National Association of Teachers of English (NATE), the atmosphere was immediately bright and hopeful.

They swept into the classroom, took hold of the space, and even made good use of the university canteen café during the break. What followed was a genuinely joyful afternoon of creativity, laughter, and thoughtful teaching from three MA Creative Writing and Education students: Niki, Elizabeth and Priyanka.

The session offered some powerful reminders about what works when teaching creative writing to teenagers. It also showed how much teenagers appreciate being welcomed into a university, given clear tools, and invited to play with language rather than fear it.

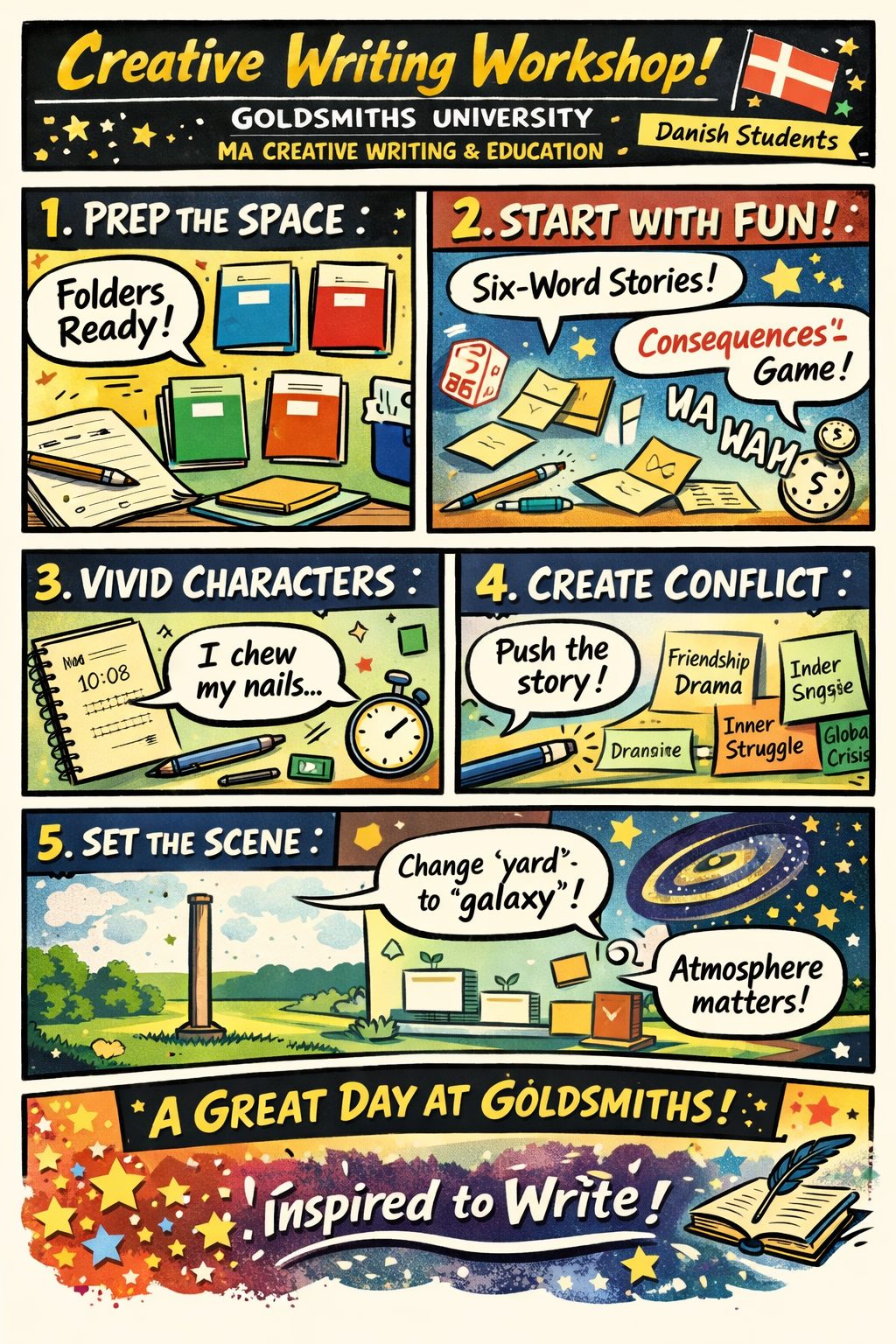

Here are five key takeaways, with insights and quotes drawn from the workshop.

1. Prepare the space with care (but keep sustainability in mind)

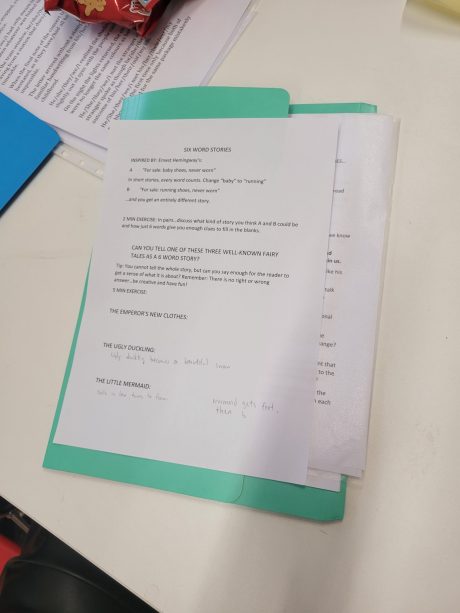

When the students arrived, the room looked like a miniature creative writing studio. Each participant had a folder containing worksheets, prompts and ideas. One of the students commented that they loved having “everything organised for us,” adding that they felt “very welcome” because the session had clearly been prepared with care.

A member of the teaching team reflected afterwards, “It’s lovely to have the folders, they’re like little textbooks,” noting how useful it is pedagogically to give students a sense of structure and ownership.

At the same time, we discussed afterwards how future sessions might balance this with sustainability – perhaps offering digital versions or reusable folders. Teenagers certainly appreciate thoughtful preparation, but they also understand (and increasingly expect) environmentally mindful teaching.

Lesson: Preparation matters, but so does modelling sustainable practice.

2. Begin with playful, low-stakes writing

Teenagers relax when the first activity feels manageable. The six-word-story task was the perfect warm-up. One teacher explained, “Every word needs to serve a purpose,” and the students were captivated by how much meaning could sit inside so few words.

But the runaway favourite was Consequences. As soon as the papers started passing around the table, the room erupted in giggles. The teachers used it to make a deeper point: “Things happen, people exist, and that’s essentially what a story is.”

The delight of the students was unmistakable; the game offered the perfect bridge from silliness to story structure.

Lesson: Play opens the door to confidence and creativity.

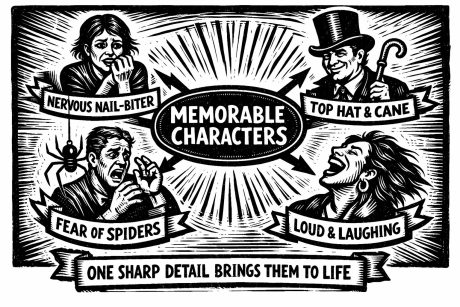

3. Teach character using one vivid, memorable detail

The character-building session encouraged students to move beyond basic physical description. As one teacher put it, “You wouldn’t describe someone you know by saying they’re eighteen with black hair… you’d say something memorable about them.”

Students quickly grasped that a distinctive habit, a flaw, a fear, or a way of speaking can make a character feel alive. One of them commented that it suddenly felt “easier to picture the person” once they had focused on a single strong detail.

Lesson: One sharp, humanising detail can do more than a paragraph of description.

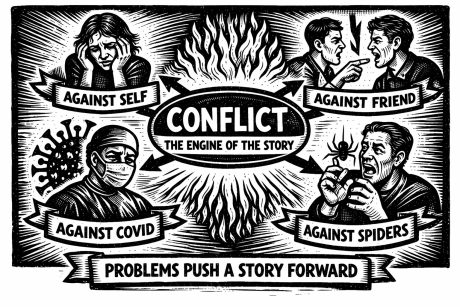

4. Use conflict as the engine of the story

The teaching team offered a clear explanation of conflict that really struck the students. Conflict, they explained, could be internal, interpersonal, or global. “You are against something,” one teacher said simply, and the teenagers nodded – from Covid to friendship rows to self-doubt, they recognised this instantly.

Groups formed thoughtful conflicts for their characters. Some were gentle and introspective; others were dramatic. What mattered was that each student saw how a problem pushes a narrative forward.

Lesson: Teenagers connect deeply with conflict when shown its relevance to everyday emotional life.

5. Let setting create atmosphere, not a travel guide

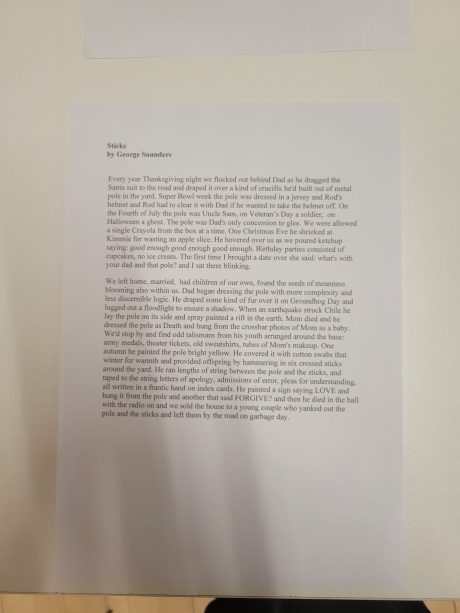

A highlight of the session was the exploration of how setting shapes tone. The students were surprised by how little information they needed to imagine a world. When asked to describe the “yard” in a George Saunders’ story (see above), they immediately pictured houses, neighbourhoods and even moods, despite being given almost no physical details about the setting, other than a description of a pole put in the yard.

The teachers emphasised that small choices carry weight. “One word can shift a whole genre,” one said, demonstrating how changing “land” to “galaxy” instantly flips a fairy tale into sci-fi.

Lesson: Encourage teenagers to think in sensory fragments rather than long descriptive passages.

A warm ending (and a poem)

To close the session, one of the teachers, Priyanka, read a poem summarising the afternoon:

once upon a time,

Priyanka

in a room very near,

a group of us gathered

with curiosity and cheer.

we were looking to learn

how to write a story short,

something that managed

to move along a plot.

we learned how to make

characters come to life

and the way a conflict

can cause stress and strife.

we found a place and time

to set our stories in,

and problems and people

to let the yarn spin.

at the end of the day when

began the setting of the sun,

we took a deep breathe

after all the activities we’d done.

and best of all, we carried home

in our pockets, the key to writing

a short story and all the tricks

to unlock it.

It was a fitting conclusion to a lively, generous workshop – and a brilliant advert for the MA Creative Writing and Education, where practice-led teaching meets joy, play, and craft.

Leave a Reply