At the very beginning of Joachim Trier’s new film, Sentimental Value, the house speaks. Or rather, it breathes, remembers, waits. A large Norwegian house in Oslo appears not just as a setting but as a presence, almost a character in its own right. It feels solid, physical, full of rooms and staircases and objects, yet also ghostly, saturated with memory. From the first moments, the film invites us to think about home not simply as a place we live in, but as something that holds, distorts, and sometimes damages the people inside it.

The death of a mother draws two adult daughters, Nora and Agnes, back into relation with their estranged father Gustav, played with aching restraint by Stellan Skarsgård. Gustav is an ageing film director who divorced their mother many years earlier. The house becomes the site where old conflicts, silences, and griefs are reactivated. What unfolds is not a story about reconciliation in any neat sense, but about learning what home making really involves when a home itself has been shaped by trauma.

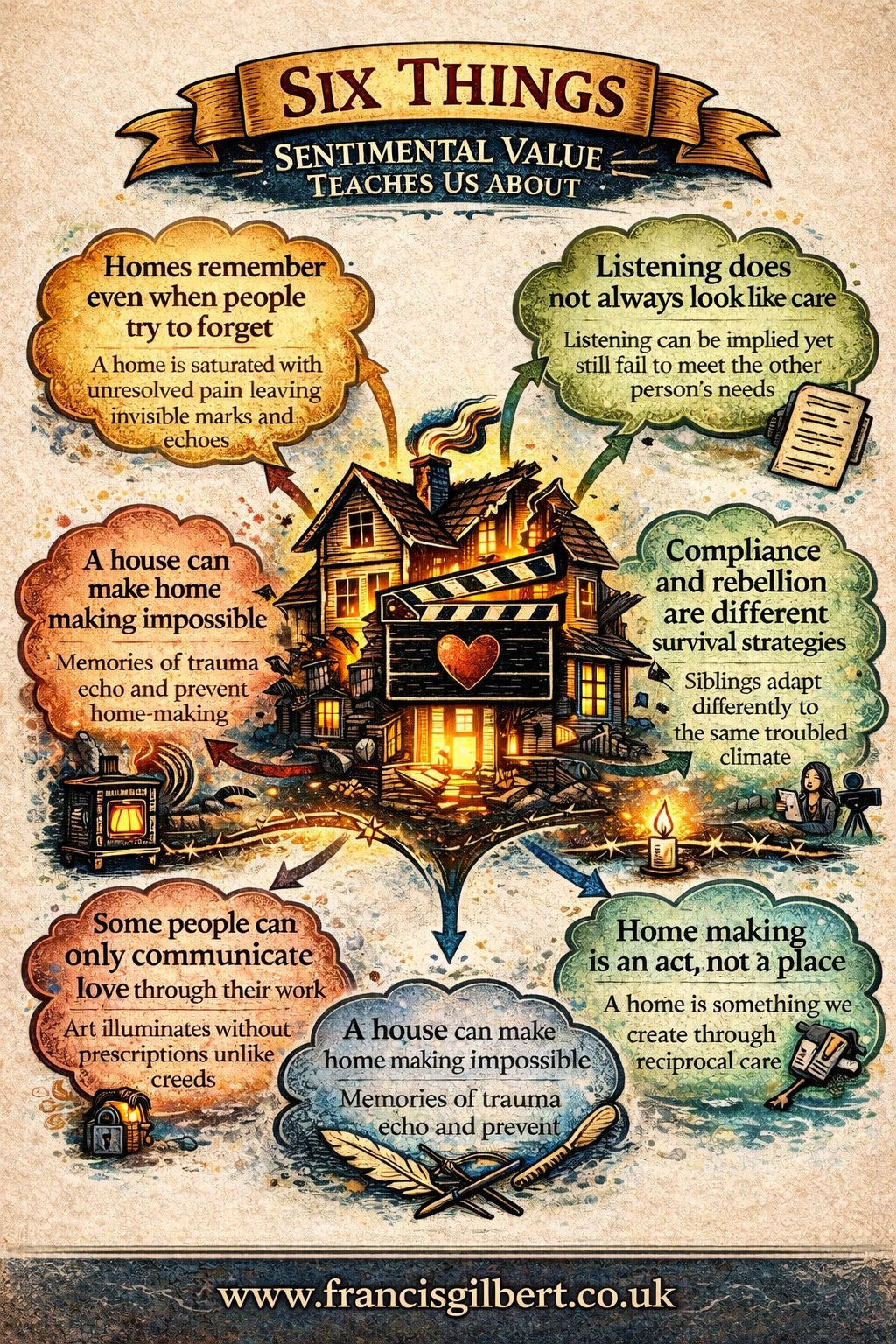

Here are six things the film taught me about home making.

1. Homes remember even when people try to forget

This house has seen too much. Gustav grew up in it, and when he was seven years old his mother killed herself there. She had been part of the resistance in Oslo during the Second World War, tortured, traumatised, and ultimately betrayed by a neighbour. The film never presents this history in a straightforward way. Instead, it emerges through montage, mise en scène, and repetition. The walls seem to carry the weight of what happened. Home making here is obstructed from the start, because the home itself is saturated with unresolved pain.

2. Listening does not always look like care

One of the most quietly devastating images in the film is Nora as a child listening through the stove to her mother, who worked as a therapist, speaking patiently and attentively to her clients. The mother listens beautifully to strangers, but her daughters experience her as emotionally distant. The house becomes a place where voices travel through walls, but connection does not quite arrive. Sound is present, care is implied, yet something essential is missing. Home making requires more than proximity or hearing. It requires being listened to in a way that recognises your particular need.

This pattern reappears later in Gustav’s relationship with Rachel Kemp, the American actor played by Elle Fanning. Rachel encounters Gustav’s work at a festival and is genuinely moved by it. When Nora refuses to play the role of Gustav’s mother, Rachel agrees to take it on. She listens carefully, tries hard to understand what Gustav wants, and approaches the role with humility and seriousness. Yet barriers remain. She performs in English rather than Norwegian, and she does not carry the history of the house, the war, or the family. Her listening is attentive, but it cannot fully cross the distance that history has created.

This could have been handled as comedy or satire, but the film refuses that tone. Instead, it becomes a quiet parable about art. Gustav communicates through film because art offers what creeds cannot. As Nietzsche puts it, “Art raises its head where creeds relax” which comes from his book Human, All Too Human (1878). In this aphorism, Nietzsche reflects on what happens as religious belief and rigid systems of doctrine lose their authority. He suggests that when creeds, understood as fixed rules and moral frameworks, begin to loosen, art takes on a new importance.

Nietzsche’s point is not that art replaces religion with another set of instructions. Rather, art offers something more subtle. Where creeds prescribe, art illuminates. Where doctrine fixes meaning, art opens it up. As the emotional and spiritual energies once directed into religion are released, they flow into art, giving it a heightened capacity to explore feeling, ambiguity, and human experience without telling us exactly what to believe or how to live.

This context matters in Sentimental Value, because Gustav’s filmmaking is not a belief system or a moral guide. It is an attempt to shed light on pain, memory, and love without resolving them. Art, in Nietzsche’s sense, does not create a home by laying down rules. It lights moments of understanding, which people may or may not be able to turn into care.

3. Compliance and rebellion are different survival strategies

Agnes’s journey becomes particularly significant when, now an art historian, she researches the archival files relating to her grandmother, Gustav’s mother. Confronting the documented reality of torture, betrayal, and resistance, she finally stands up to her father. This moment feels crucial, not just personally but culturally. Trier is quietly investigating what happens to families, and to homes, in societies with a recent history of torturing their own people. The trauma does not end with the event itself. It seeps into domestic life, into silence, compliance, and emotional distance. It is hard not to feel the pertinence of this now, in an age marked by the rise of fascism, by us and them politics, and by the renewed normalisation of cruelty in public life.

As children, the sisters responded differently to this environment. Agnes was the compliant one. She even appeared in one of Gustav’s films, playing a fleeing child during the Nazi occupation, already inhabiting history as something performed rather than spoken. Nora, now an actor, resisted him more openly, refusing to become a vessel for his unresolved past. The film does not judge either response. Instead, it shows how siblings adapt in different ways to the same emotional climate.

What Sentimental Value suggests is that home making later in life involves recognising these differences with generosity. It requires refusing to replay the old roles of compliance and rebellion, and instead allowing space for each person’s way of surviving to be understood. Only then can something like a home, fragile, provisional, and human, begin to form.

4. Some people can only communicate love through their work

Gustav has written a new script, which he believes is his best yet. It is about his childhood and his mother. He wants Nora to play her. She refuses, furious that he can only engage with his family through filmmaking, through scripts and roles, rather than being present. The film slowly reveals that this limitation is real, but it is also his language. He is not withholding love so much as trapped inside a mode of expression. Home making sometimes requires learning the imperfect languages people use to show care.

5. A house can make home making impossible

This is not a cosy film about reclaiming a family house. The Oslo home is lonely, echoing, filled with memories of fights, absence, and despair. It resembles Philip Larkin’s poem Home is so Sad, where the house remains shaped to the comfort of the last to leave, bereft, with no heart to turn again to what it started as. In Sentimental Value, the house cannot be redeemed. It is not the solution. It is the problem.

6. Home making is an act, not a place

By the end of the film, the sisters make a home for themselves, but not by fixing or reclaiming the house. They do it through understanding how they love each other. The film shifts our sense of home away from architecture and towards relationship. Home becomes something created moment by moment through reciprocal care, feeling safe, being listened to, and allowing complexity. It is not permanent or solid. It is practiced.

The film’s metafictional play, a film within a film, script readings that blur into lived experience, keeps us uncertain about what belongs to Gustav’s work and what belongs to the “real” narrative. This uncertainty feels purposeful. Gustav’s life and art are inseparable, much as the house is inseparable from the trauma it contains. There are clear echoes of Bergman here, Cries and Whispers, Fanny and Alexander, the sisters, the rooms, the weight of childhood grief. There are also resonances with Joachim Trier’s earlier films, including The Worst Person in the World, with Renate Reinsve again offering extraordinary emotional precision.

For me, Sentimental Value is Trier’s most mature film so far. It understands that home making is not about repair or resolution, but about learning how to stay present with what cannot be fixed. In that sense, it feels both deeply sad and strangely hopeful.

As Larkin writes,

Home is so sad. It stays as it was left,

Shaped to the comfort of the last to go

As if to win them back. Instead, bereft

Of anyone to please, it withers so,

This film accepts that sadness, and then gently, painfully, shows us another way to belong.

Leave a Reply