On Monday 29 September 2025 I had the pleasure of leading a workshop as part of Ecology in the Art Curriculum: An Interdisciplinary CPD Event at Goldsmiths. The afternoon was convened by Helen Bickford, Education Officer at the British Ecological Society (BES). The BES is the oldest ecological society in the world, with thousands of members worldwide, and it was a privilege to collaborate with them. The event was hosted with colleagues from the MA Art and Ecology and the Centre for Arts and Learning at Goldsmiths, creating a rich interdisciplinary space where teachers, trainee teachers, artists, and researchers could meet.

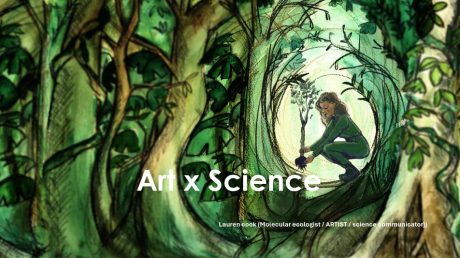

Helen opened the afternoon with characteristic warmth and clarity, before handing over to speakers to the Head of MA Art and Ecology, Ros Gray. Later on, after our workshops Dr Lauren Cook shared her work on embedding ecological science and diagrams within scientific work. It was a brilliant example of how science and the arts can intersect. My own contribution, ParklifeworkshopBES2025.pptx, asked delegates to explore how multimodal creative practice can generate ecological insight and civic action.

1. Begin with breathing, end with agency

We began with a few breaths: a 7–11 pattern, in for seven, out for eleven. The effect was immediate. One delegate whispered afterwards, “I don’t usually do anything like this… but I wanted to see if it could work for my classes.” That small act of pausing gave everyone permission to let go of the day’s rush. From there, the visualisation carried us into an imagined or remembered park. A participant from an architecture background described how, during the exercise, she found herself noticing “the way we always had to think about ecology when designing buildings, the wildlife we had to take care of.”

When delegates opened their eyes, the room felt different: quieter, but also more alert. Pair sharing kept the stakes low, and soon teachers were comparing how they might adapt the exercise for GCSE groups or primary art clubs. The structure mattered: soothe, sense, share, and then shift towards action.

2. Multimodality reaches the pupils that prose leaves behind

When we moved into free writing and sketching, the variety of responses was striking. Some picked up pens straight away; others sketched textures, pathways, or trees. One teacher laughed as she showed her neighbour a quick drawing: “I’m not a writer, but I can map what it felt like.” This confirmed what Parklife had taught us across London schools—that multimodality opens doors.

A participant with experience in community gardening noted, “We’ve worked with local people to source and green spaces. I want to connect that to curriculum planning.” Her comment underlined the value of giving pupils multiple modes to express what they notice, whether that is a collage, a poem, or a video.

3. Stories make resilience tangible

Halfway through I told the story of the cracked pot that leaks water on the climb up the hill, watering flowers along the way. As I spoke, people nodded. One delegate who works in outdoor learning later reflected that it captured what she sees daily: “Imperfections often carry hidden strengths.”

This was exactly the purpose of Parklife’s storytelling strand. When pupils at Deptford Green wrote about their fears of walking through parks at night, repeating the refrain “your safety matters,” they were not only expressing anxiety but building solidarity. In our workshop too, story gave us a way to talk about resilience without flattening it into a slogan.

4. Perception and reality must meet in public

Safety dominated the discussion, just as it had in our school projects. One trainee teacher leaned over and asked, “Do you go back and measure the impact—was that built into the project?” It was a perceptive question. Feelings of risk are real and deserve respect, but they can distort decisions unless balanced with evidence.

In Parklife we convened police officers, councillors, and health workers to meet pupils face to face, test perceptions against statistics, and design practical solutions—better lighting on winter paths, new water fountains, a wildlife corner. Delegates in the room saw instantly how they might use the same model, pairing what their students feel with what local data shows, and then letting them present findings to those in power.

5. Change travels through networks, not slogans

Perhaps the strongest reminder came at the close. As we gathered thoughts, one participant said she was “going to take the visualisation drawings back into the classroom, to help students re-engage with that space positively.” Another teacher described how she hoped to set up a small journal project with her pupils, mapping safe and unsafe routes around the school. These were not abstract hopes; they were first steps in building networks.

Parklife succeeded by helping young people meet councillors, park managers, and user groups, then encouraging them to set modest, visible goals and follow through. Delegates saw that incremental advocacy—starting small, tracking progress, linking with allies—works.

Why this matters

The CPD event reminded me why interdisciplinary work matters. The British Ecological Society’s commitment to education, combined with the creativity of the MA Art and Ecology and the Centre for Arts and Learning, created the perfect conditions for cross-fertilisation. Delegates brought perspectives from architecture, outdoor learning, teaching, and research; they left with sketches, words, and plans to adapt the exercises in their own contexts.

As I suggest in The Mindful Creative Writing Teacher, small rituals that steady attention can transform learning; they also make it easier to move from noticing to acting in humane, ecologically aware ways. I left grateful—for Helen Bickford’s leadership, for the oldest ecological society in the world standing alongside art and education, for my colleagues at Goldsmiths, and for the teachers and trainee teachers who came ready to imagine and to act.

Francis Gilbert October 2025