On the evening of 26 June 2025, Gabriel Troiano and I co-facilitated a two-hour workshop at Goldsmiths exploring the transformative intersection of mindfulness and creative writing. Gabriel, an alumnus of the MA in Creative Writing and Education, brought a calm, generous presence as we guided participants through object meditation, freewriting, and character creation. The session was based on core practices outlined in my recent book, The Mindful Creative Writing Teacher (Gilbert 2025), which explores how attention, acceptance, and ethical presence can support meaningful writing practices.

This blog draws on the workshop and extends its learning with key insights, powerful participant contributions, and relevant pedagogical theory.

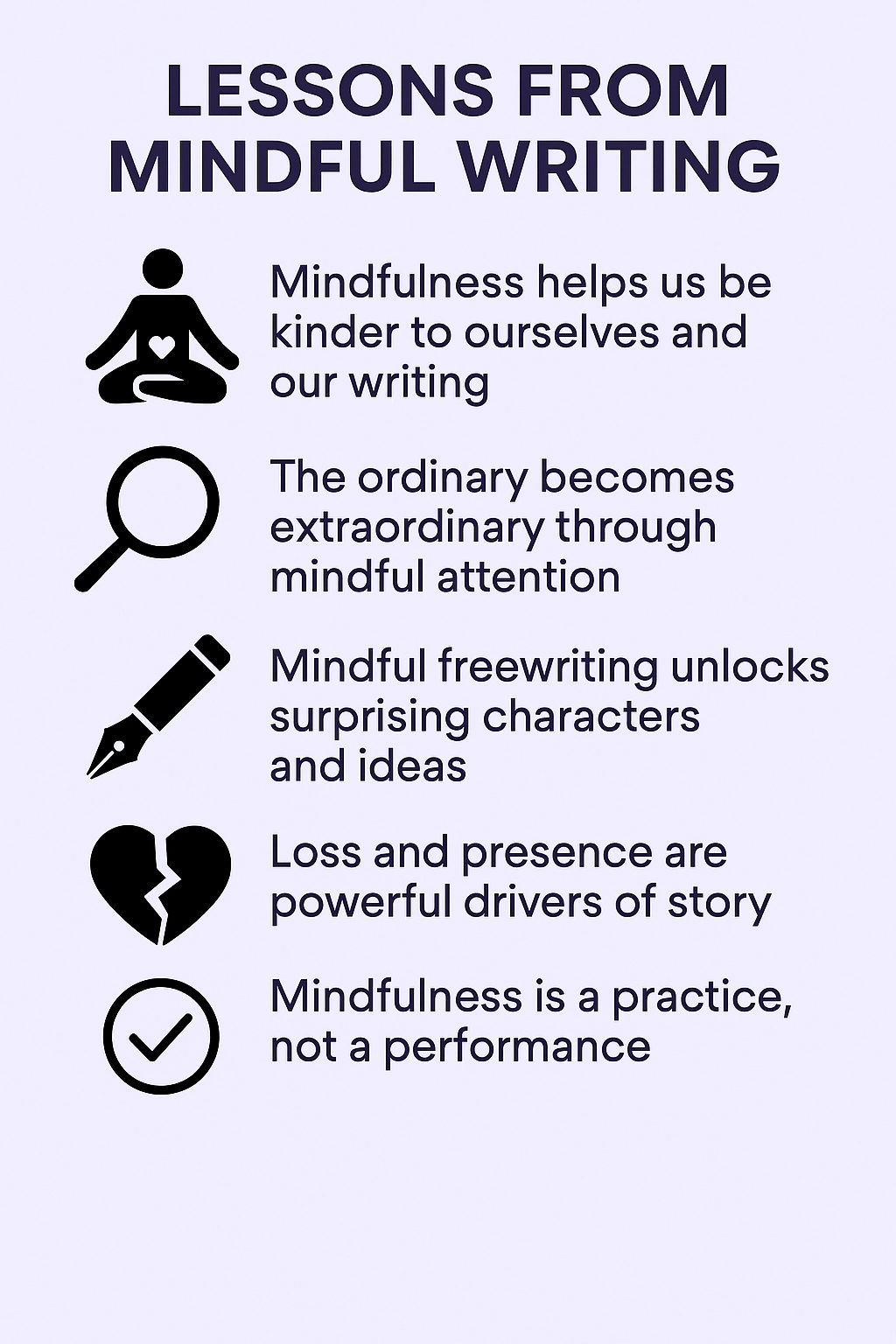

1. Mindfulness helps us be kinder to ourselves and our writing

Many writers struggle with the paralysing force of the inner critic. Gabriel reflected on his own experience: “I was always very anxious. Mindfulness helped me realise I don’t have to push so hard. It taught me to reframe my thoughts or just see them for what they are. They’re just thoughts.”

This ability to pause, observe, and re-centre is central to mindful writing. As one participant put it, “I didn’t realise I could write so much in one sitting. Once I stopped judging every line, it just flowed.”

In The Mindful Creative Writing Teacher, I show how freewriting enables this shift. It opens a gateway into the present moment and encourages writers to stay with their words, however clumsy or surprising they may be. Freewriting creates space for both clarity and confusion, for insight and struggle. As I explain, “Freewriting is an exercise in permission. It grants the writer freedom from the inner critic and from the need to produce something polished or perfect” (Gilbert 2025, p. 43).

2. The ordinary becomes extraordinary through mindful attention

One of the most moving moments in the session came when participants were invited to observe an everyday object and write about it using all five senses. These objects ranged from a Kindle to a pair of earrings, from a tissue packet to a red lipstick.

After observing her lipstick, one participant wrote: “I’ve kissed this so many times. It’s bitten, worn, blessed. Lost and found. One day I dropped it in Leicester Square and couldn’t stop thinking about it. Who would find it? Would they wear it? Would we be kissing the same stranger?”

Another reflected on their tissue packet: “My brother used to torment me when I sneezed. These tissues are mine now. I carry them to protect myself. They’re my shield.”

This approach aligns with what I describe as mindful noticing in my book. It is not about extracting metaphor or meaning for its own sake, but rather dwelling fully with the object in its specificity. As I write, “Mindful writing starts with presence. It values the immediate, the material, the small. In this space, the ordinary becomes luminous” (Gilbert 2025, p. 65).

3. Mindful freewriting unlocks surprising characters and ideas

Building on the object meditation, we asked participants to create a character who carried all the workshop objects. The results were extraordinary. Despite working from the same materials, each person produced wildly different creations.

One participant invented a woman called Lola, a drag queen from Liverpool: “The lipstick is the youth she puts on. The tissues are for drying her tears before and after the show. The Kindle helps her when she forgets her lines. The earrings were stolen from her mother, who she barely speaks to.”

Another created Daniel, a former drag performer in Eastern Europe who sips pink soda in her garden and writes her name in a sketchbook to remember who she was.

This speaks to the radical potential of freewriting. It is not a warm-up; it is generative. It allows ideas to emerge from the subconscious, from silence, from sensory memory. As I explain in Chapter 10, “Freewriting invites the writer to improvise with identity, narrative, and form. It disrupts surface-level thinking and helps access deeper emotional truths” (Gilbert 2025, p. 44).

4. Loss and presence are powerful drivers of story

In the final exercise, participants wrote scenes where their character lost one of the cherished objects. This simple premise, losing something meaningful, unlocked profound emotional responses.

One participant wrote: “She cannot find the lighter. She froze, frantically searching the grass, the table, the cushions. It was her only connection to that old life.”

Another imagined a character on a plane, devastated at having left their Kindle behind:

“I can picture it exactly. Propped on the edge of the chair, barely balanced. The shadow of the building never reached it. I was halfway through Capital. If only my dad hadn’t rushed me.”

As I note in my book, writing about loss is one of the most fertile creative territories. The missing object becomes a symbol for larger anxieties and absences.

“Mindful storytelling often begins not with resolution, but with rupture. A broken object, a forgotten item, an unanswered message, these moments are the entry points for presence” (Gilbert 2025, p. 42).

5. Mindfulness is a practice, not a performance

A vital takeaway from the session was that mindfulness is not something ornamental or decorative. It is not something you add onto a lesson or apply like a balm. It is a way of being, of noticing, of relating.

This insight builds on C. T. McCaw’s important distinction between thin and thick mindfulness. Thin mindfulness is instrumental; it soothes stress or enhances productivity without questioning the structures that produce suffering. Thick mindfulness, by contrast, is ethical and situated; it attends to context, systems, and embodiment (McCaw 2019).

As I explain in the introduction to my book, “A thick approach to mindfulness does not ask students to calm down and carry on. It invites them to ask, what do I notice, what do I need, and what do I want to express” (Gilbert 2025, p. 19).

Participants understood this deeply. One noted, “It’s not just about calming down. It’s about being present with what’s happening, good or bad, and finding a way to respond to that with care.”

Final reflections

This workshop showed us, again and again, that mindfulness and creative writing do not just work well together, they need each other. Mindfulness grounds us. Writing gives us voice. Together they offer a way to live more attentively, ethically, and imaginatively.

As Gabriel concluded, “Creative writing is often seen as solitary, but today we created and wrote mindfully together. That was really fun.”

Fun, yes. But also radical, transformative, and unforgettable.

Further reading

Gilbert, F. (2025) The Mindful Creative Writing Teacher. London, FGI Publishing: https://www.francisgilbert.co.uk/2025/05/the-mindful-creative-writing-teacher/

McCaw, C. T. (2019). Mindfulness ‘thick’ and ‘thin’— a critical review of the uses of mindfulness in education. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1667759

Leave a Reply