I’m feeling quietly proud, and also rather fired up, because an article I co‑authored with Anna Stewart of i2Media has just been accepted into the Goldsmiths research repository and is a chapter in a new book Ecologies in Practice and Learning, Arts Interventions in the Earth Crisis, edited by the creative and multitalented academic, Dr Miranda Matthews, who is a colleague of mine in Education at Goldsmiths.

The article, How can we help young people improve their local environments? How can they become agents of change?, grew out of the Parklife project, a collaboration between university students, school pupils and local communities. It asked a deceptively simple question. What happens if we stop treating young people as a problem in parks, and instead invite them to research those parks creatively and critically?

What followed surprised even us.

Young people aged eleven to fourteen became co‑researchers. They wrote poetry, filmed their park using 360‑degree cameras, made artwork, conducted surveys, interviewed councillors and park managers, and then stood up in front of adults and told them, plainly and powerfully, what needed to change. And things did change. Lighting improved. Litter schedules were upgraded. A water fountain was installed. A community garden was created.

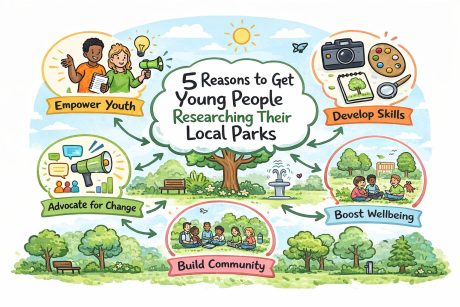

So, here are five reasons why getting young people researching their local parks is not just a nice idea, but an urgent one.

1. It flips the deficit narrative

Too often, public discourse frames young people in parks as a problem. Loitering. Anti‑social behaviour. Noise. The Parklife research showed something very different. When young people are invited in as researchers rather than policed as risks, they become thoughtful, ethical and highly perceptive observers of place.

In our project, pupils spoke eloquently about fear, safety, beauty, neglect and care. One young researcher said that for the first time they felt their voice was being heard by people who could actually make change happen. That sense of agency matters. It counters the idea that civic responsibility is something you acquire in adulthood. In reality, it grows when you are trusted.

2. Creative research generates real impact

This wasn’t research locked away in a report. The creative outputs were the research. Poems, paintings, films and photographs generated what we describe in the article as powerful affective flows. In other words, they moved people.

At the project’s advocacy event, a poem about litter, fear and loss in the park was read aloud by a pupil. Councillors and park managers were visibly affected. Promises were made on the spot, and crucially, they were kept. The article documents these outcomes in detail fileciteturn0file0.

There is a lesson here for anyone involved in education or policy. Evidence does not have to mean spreadsheets alone. Feeling is not the enemy of rigour. When research is creative, it can cut through defensiveness and reach decision‑makers in ways that conventional reports often cannot.

3. Parks become classrooms without walls

Parks are complex ecological and social spaces. They are assemblages of people, animals, plants, infrastructure, memories and power relations. By researching parks, young people learned about ecology, local politics, data collection, ethics, collaboration and advocacy, all in one place.

They conducted surveys on perceptions of safety, discovering that younger pupils felt significantly less safe than older ones. They interviewed police officers and park users, learning to hold statistics alongside lived experience. They used 360‑degree cameras to imagine the park from an animal’s perspective, producing images that made viewers rethink litter and care.

This is education at its best. Interdisciplinary, situated and meaningful.

4. It reconnects young people to place and belonging

Many adolescents feel alienated from local green spaces once playgrounds no longer cater for them. Parklife reversed that drift. Through repeated learning walks and creative engagement, young people developed a renewed relationship with their park. They noticed details they had previously ignored. They articulated grief after a young person was murdered there. They expressed pride when changes were made.

Belonging is not abstract. It is built through attention and care. Researching a place teaches you that it is not neutral, and that you have a stake in it.

5. It shows what socially engaged research can be

I’m pleased that this article is being considered within the REF framework because it demonstrates a form of research that is collaborative, ethical and impactful. University students did not swoop in as experts. They worked alongside pupils as equals, sharing skills and learning in both directions. Knowledge moved rhizomatically, not hierarchically.

For me, this speaks to a broader argument about what research in education should be doing right now. In an era of ecological crisis and democratic fragility, we need research that helps young people see themselves as agents of change, not future citizens waiting their turn.

That is why this matters.

If you’d like to read the full article, you can access it either below, or via the Goldsmiths repository here, and it has also been published as a chapter in the Springer volume Ecologies in Practice and Learning: Arts Interventions in the Earth Crisis. It documents the methods, theory and outcomes in much more detail, and I hope it will inspire other teachers, researchers and communities to try similar approaches.

And yes, I’ll admit it. I’m proud that this work is being recognised. Not because of the metric, but because it shows that creative, collaborative research with young people belongs at the heart of how we think about education, environment and social change.

Let’s put young people back in the picture. Starting with the parks right outside their schools.

The full article in its copyright free version is here:

Leave a Reply