This past week, I delivered what proved to be one of the most enriching and successful sessions of the summer term for students on the MA in Creative Writing and Education. It was also attended by teachers, researchers, and creatives from varied professional backgrounds. The session—Designing Effective Creative Writing Lessons—offered a practical and pedagogically-grounded framework for lesson planning using my CASTERS model. This blog captures some key takeaways, participant reflections, and the core principles we explored.

“What I really appreciated was how honest and reflective the session was. We weren’t just given techniques—we explored what it means to teach writing in a way that’s humane and responsive.” – Participant

1. Understand the Pit: Designing for Productive Struggle

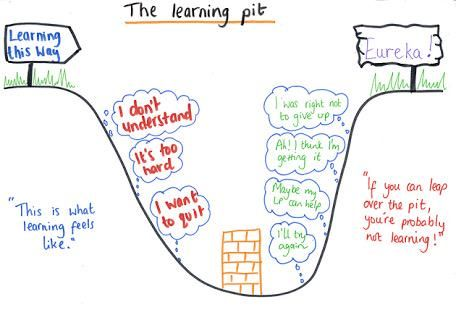

A key concept underpinning effective creative writing pedagogy is James Nottingham’s metaphor of the “Learning Pit” (2015). The pit represents the zone where learners encounter cognitive conflict, confusion, and challenge—what educational theorists from Vygotsky onwards have identified as the crucible of deep learning. It’s in this space that learners question assumptions, wrestle with complexity, and begin to construct new understandings.

For teachers, it’s vital to understand the pit not as a place to avoid, but as a space to design for. We must create learning experiences that offer just enough difficulty to challenge learners, without overwhelming them—tasks pitched within their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), where they can succeed with guidance and peer support (Vygotsky, 1978; Biggs, 2003).

In our seminar, we explored this by reflecting on our own moments of struggle—as both writers and educators. These stories became vivid case studies of what it means to design from inside the experience of learning.

One participant recalled delivering a dialogue-writing workshop at the British Library when her slides failed and a probing question disrupted her plan. She reflected:

“At first I felt like a fraud. But I realised I could let go and follow the energy in the room. By adapting, the session improved—it became more honest, more responsive.”

Another participant described tailoring a writing process for a Year 7 student with both SEN and EAL needs. The student wanted to write a novel, but conventional structures didn’t fit. The teacher created a staged, booklet-based process that honoured the student’s vision while offering scaffolding and feedback:

“It forced me to think more carefully about pace, sequence, and support. I couldn’t just deliver content—I had to co-create a path out of the pit.”

These examples illustrate that understanding the pit as a teacher means embracing vulnerability, unpredictability, and responsiveness. It also means designing in ways that scaffold the learner’s struggle without short-circuiting it—an approach aligned with mindful pedagogy (Gilbert, 2021; McCaw, 2020).

As Dylan Wiliam notes:

“If all students respond correctly, the question is too easy. If none do, it’s too hard. The sweet spot lies in designing tasks that make them think.”

2. Use the CASTERS Framework: A Mindful Model for Lesson Design

To support mindful and effective creative writing pedagogy, I introduced the CASTERS model—an acronym designed to help educators shape lessons that are engaging, reflective, and grounded in sound educational theory. Each stage of CASTERS prompts teachers to think holistically about the design of their lessons, balancing structure with creativity and challenge with care.

The seven key elements of CASTERS are:

- Connect

- Activate prior knowledge and assess

- Set goals and learning activities

- Timings

- Effort focus

- Reflect

- Set independent learning

We explored each component through practical activities—including a lively diagrarting session, where participants mapped their lesson ideas visually using sketches, diagrams, and creative prompts.

To help internalise the model, I shared a poem I’d written to bring the CASTERS spirit to life. Here are selected stanzas that encapsulate the heart of each element:

C is to Connect, to forge the flame,

To welcome each student, to call them by name.

With warmth in our gaze and kindness our guide,

We build the trust where bold words can reside.

Connecting is more than an icebreaker—it’s the emotional and relational groundwork for any creative writing experience. This might involve greeting students by name, inviting them to bring objects or memories into the room, or simply asking what energy they are bringing that day.

A is to Activate, draw from the well,

Of memories, senses, the stories they tell.

We assess what they know, not to test or confine,

But to honour their path and spark the next line.

Activating prior knowledge is essential. Rather than assuming a blank slate, we invite learners to retrieve what they already know or feel about a topic. It’s formative and diagnostic: What concepts, experiences, or emotions are they already carrying?

S is to Set goals, to name what we seek—

A scene, a character, a voice that will speak.

We frame our intentions, map out the way,

Through prompts and through purpose, we shape the day.

Good goals make purpose visible. They help learners—and teachers—understand why they’re doing an activity. It might be to develop voice, explore conflict, or work toward a performance or publication. These goals should be specific, meaningful, and open enough to allow for individual expression.

T is for Timings, not rigid but clear—

A rhythm, a beat to hold focus near.

With space to be playful and time to refine,

We honour the craft in each student’s line.

While creativity doesn’t run on a stopwatch, thoughtful time management helps maintain focus and flow. Sketching out micro and macro timings (e.g. 5-minute bursts, full workshop arcs) keeps lessons structured without being oppressive.

E is Effort focus, the heart of our creed,

We praise the persistence, not just the speed.

For writing is messy, a wrestling art,

And grit is the ink that flows from the heart.

This is a key principle of mindful pedagogy. Rather than rewarding performance or polish alone, we highlight the process: the struggle, the re-drafting, the moments when learners stay with a difficult task. Praise becomes formative, not final.

R is to Reflect, to pause and to see

What moved us, surprised us, what we came to be.

Through sharing and silence, we circle back round,

And in that deep stillness, new truths are found.

Reflection is essential. It turns experience into learning. In our seminar, participants spoke about the power of reflecting both in and on action—whether journalling, sharing aloud, or simply asking “What did I discover about myself today?”

S is for Set independent learning anew,

To carry the spark and see it shine through.

To journal, to edit, to write beyond class—

A future where self-trust will always amass.

Finally, learners need space and motivation to continue writing on their own. The goal isn’t homework for its own sake—it’s the cultivation of a writing habit, of inner voice, of self-trust.

The CASTERS model offers a flexible but intentional design framework that blends educational theory (Biggs’ constructive alignment, Vygotsky’s ZPD, and mindful pedagogy) with the lived realities of creative classrooms. It helps us move from intuitive teaching to reflective practice—while staying human, playful, and bold.

“So let us be CASTERS, lighting the page,

Guiding each student from margin to stage.”

3. Teach Mindfully, Not Mechanically

A central theme of the seminar was the distinction between mindful and unmindful approaches to teaching creative writing. A mindful teacher embraces struggle as a vital part of the process, while an unmindful one often attempts to sidestep it—focusing instead on coverage, compliance, and control.

Mindful teaching is defined not by methods alone, but by attitude and awareness. It includes:

- Embracing confusion and struggle as normal and generative

- Modelling vulnerability and reflection (e.g., sharing moments of personal difficulty in writing)

- Normalising difficulty through metaphors like “the learning pit”

- Designing emotionally responsive, culturally aware, and reflective learning spaces

- Encouraging open questions like “What are you bringing into the room today?” or “When did you last feel stuck in your writing?”

By contrast, unmindful teaching often manifests in mechanical or performative ways. It might include:

- Avoiding discomfort: saying “Don’t overthink it” or “Just get it done” when students are stuck

- Delivering overly rigid, content-heavy lessons with no space for reflection or emotional connection

- Dismissing emotional responses as irrelevant (“That’s not what we’re learning today”)

- Prioritising assessment objectives over student engagement, identity, or wellbeing

- Using generic, disconnected tasks (e.g., “Fill in this plot structure worksheet” without discussion or creative input)

“I’ve taught for years, but I’m still stuck in rigid modes—teaching to assessment objectives, not students’ lives. This session reminded me that creative writing can reconnect us.” — Participant reflection

We discussed how unmindful approaches are often the result of systemic pressures—curricula that are overloaded, accountability demands, or lack of training in inclusive practice. But we also affirmed that even small acts of mindfulness—taking a breath before a lesson, beginning with a poem, allowing students to write without being marked—can radically shift the atmosphere.

As the CASTERS model shows, mindful teaching isn’t about abandoning structure—it’s about designing with awareness of who your students are, what they need, and how writing can help them grow.

4. Normalise Struggle, Model Recovery

One of the most powerful insights to emerge from the seminar was the idea that a mindful creative writing teacher not only normalises struggle—but also models recovery. In other words, we don’t just teach students to accept difficulty—we teach them how to move through it.

We discussed how the discomfort of “not knowing” is often where the deepest growth happens. But this only becomes meaningful if learners see that struggle is not failure, and that recovering from confusion, false starts, or blocks is part of the creative process—not something to be ashamed of or rescued from.

“My best creative writing sessions happen when I let students linger in the mess,” one teacher reflected. “It’s terrifying—but it’s where real growth happens.”

A mindful approach offers tools to sit with uncertainty, and then gently scaffold a way forward. This might include:

- Giving students time and space to write without judgement (e.g., through freewriting or silent journaling)

- Sharing your own writing missteps or moments of confusion as a teacher (“I got really stuck at this point too…”)

- Using metaphors like the Learning Pit to help students visualise recovery: the fall, the wall, the climb out

- Encouraging reflection: “What helped you move forward?” “What did you discover while stuck?”

- Reframing revision as creative recovery, not correction

“I was in the pit for two years,” one student from the Philippines shared, speaking about navigating a literature degree in her second language. “Eventually I realised I had developed strategies no one else had—because I had to. That became part of my writing voice.”

By modelling recovery as a normal, even essential part of the creative process, teachers help students build resilience. They learn that doubt, fatigue, or lost momentum don’t mean they’ve failed—they mean they’re writing.

In mindful classrooms, recovery is not silent or invisible. It’s something we name, support, and celebrate.

5. Design Lessons That Align: Making Learning Coherent and Purposeful

An essential concept we explored in the seminar was constructive alignment, a term coined by educational theorist John Biggs (2003). This principle lies at the heart of effective, mindful lesson design.

In essence, constructive alignment means ensuring that your learning objectives, teaching activities, and assessment methods all work together, rather than operating in isolation. Each element should serve the same purpose: helping students achieve meaningful, intended learning outcomes.

Constructive refers to the idea that learners construct meaning through active engagement and experience, drawing on constructivist theories of learning (e.g. Vygotsky, Piaget).

Alignment means that everything in the lesson—what students are asked to do, how they’re guided, and how their learning is assessed—should be purposefully connected.

“The CASTERS framework helped me see how each lesson is part of a whole,” one participant reflected. “I can now trace a thread from connection to reflection.”

What does this look like in creative writing?

- Take, for example, a lesson sequence where the objective is to develop a distinctive character voice. If that’s your goal, then:

- Your activities might include reading a dramatic monologue, discussing voice, and drafting a monologue from the perspective of a forgotten object (like a lost shoe).

- Your assessment might ask students to revise their monologue with feedback, then submit a 250-word piece demonstrating consistency of tone and voice.

- You might build in reflection prompts—“Where did you struggle to find your character’s voice?”—and set independent learning that deepens the same skill (e.g. writing a second monologue from a different object).

- When alignment is strong, students experience the lesson as purposeful. They understand why they’re doing what they’re doing—and what success looks like. This supports motivation, confidence, and retention.

By contrast, in unmindfully designed lessons, there may be a disconnect:

- Objectives that aim for creative expression, but activities that drill technical terms.

A worksheet on similes assessed with a rubric on structure.

Writing tasks with no space for feedback or reflection. - In the seminar, participants created beautifully aligned sequences such as:

- Writing character sketches using fan fiction as a familiar and motivating form

- Exploring perspective by rewriting a well-known story from the antagonist’s point of view

- Using writer’s circles to revise and reflect collaboratively before submission

- These sequences weren’t just creative—they were coherent, guided by intentional connections from Connect to Set independent learning in the CASTERS model.

Constructive alignment invites us to teach with presence, purpose, and courage—just as we ask our students to write.

6. Create Community and Independence: Publishing as Pedagogy

Our final focus in the seminar was on the dual pillars of creative writing development: community and independence. For learners to flourish, they need both the encouragement of shared purpose and the space to discover their voice in solitude.

We discussed how community can take many forms: small workshop groups, buddy systems, school clubs, intergenerational writing spaces, or even digital collectives. But one particularly powerful anchor for community is publishing.

- Publishing doesn’t have to mean a book deal or high-stakes competition. It can mean:

- A class anthology

- A shared webpage featuring students’ writing

- A zine produced collaboratively

- A community showcase, exhibition, or reading

- A private archive or portfolio, even if only shared among peers

These kinds of projects give learners a real audience, a shared deadline, and a collective purpose. They support constructive alignment, motivating students to take ownership of their writing journey and revise with intention.

“I want to build spaces where people feel they belong,” one participant shared. “Where writing becomes a tool for life—not just for assessment.”

Publishing can be especially transformative for marginalised learners—those in informal settings, those with SEN or EAL needs, or those disillusioned with conventional schooling. Giving these learners the chance to shape something tangible and meaningful helps restore agency and voice.

For more ideas, case studies, and resources on publishing in creative writing education, you can explore this section of my website, which offers practical advice and reflections on how publishing can be embedded in teaching practice.

At the same time, independence matters. We talked about the need to make space for:

- Silent writing time

- Journalling

- Reflective pauses

- Optional sharing

- Writing that doesn’t have to be marked or published

A mindful teacher supports learners to write for themselves, not just for others. The balance between collective publishing and personal exploration is what makes creative writing pedagogy so rich.

In CASTERS terms, this is the final “S”—Set independent learning—but really, it’s also a beginning. It’s the part where the spark we light in the classroom continues beyond the walls, into the writer’s lifelong journey.

What Next?

Participants were then invited to design a sequence of 2–3 constructively aligned creative writing lessons, and to trial them at our Reciprocal Teaching Day on 4 July—an opportunity to try out lesson ideas in a safe, supportive space.

If you attended and would like to share your reflections or co-develop a lesson, please comment below or email me directly.

I’ll post more blogs soon on recent sessions covering uncreative writing, safeguarding, and more.

Warm thanks to everyone who came and shared so generously.

Let’s stay connected—and keep casting!

Dr Francis Gilbert

Head of MA Creative Writing and Education

Goldsmiths, University of London

References:

- Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for Quality Learning at University (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

- Gilbert, F. (2021). “Research-informed approaches to teaching creative writing online.” Writing in Education, Issue 83.

- McCaw, C. T. (2020). Thick and Thin Mindfulness in Education. Mindfulness and Education, 15(1), 1–19.

- Nottingham, J. (2015). The Learning Challenge. Corwin.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Harvard University Press.

- Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment. Solution Tree Press.