We were privileged to welcome back Nick Bailey, an alumnus of the MA in Creative Writing and Education, to share his experiences of the publishing world, from self-publishing to securing an agent and working with a small independent press. What followed was far more than an industry talk, it was part pep talk, part group therapy. Here are six takeaways we’re still thinking about.

1. Self-Publishing Offers Creative Control, But Finding Readers Is Hard Work

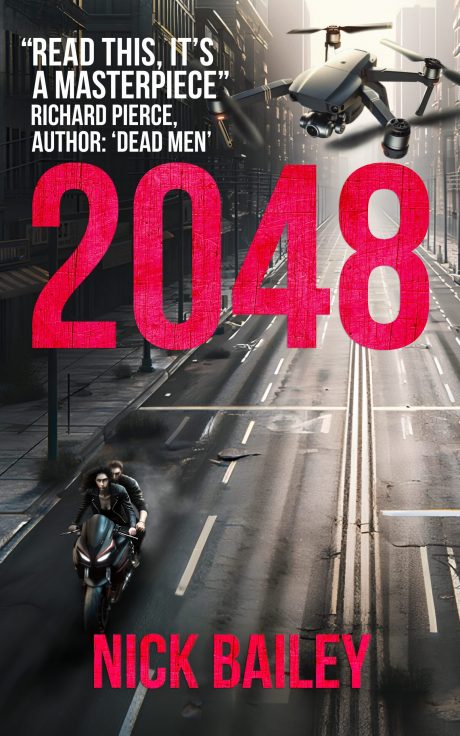

Nick’s novel 2048 started as a bold experiment: part political satire, part near-future tech nightmare, part personal reckoning. It didn’t slot neatly into any category, and that was the point. What was most instructive was how he approached this as a full-spectrum publishing exercise.

As Nick explained, self-publishing means doing it all:

“You’re not just the author, you’re the designer, publicist, typesetter, and PR team.”

Here’s how he did it:

a) Formatting and Uploading:

He went with Kindle Direct Publishing, Amazon’s self-pub platform, for both the ebook and print-on-demand paperback. The Kindle bit was fine; the print layout nearly broke him.

“The Kindle version was relatively straightforward, but the print version involved laying out every page. I hadn’t realised just how much work it would be.”

b) Creating a Cover and Blurb:

He designed a professional looking cover, gave the book a blurb, and took full control over metadata, categories, pricing, keywords.

“It’s a different skillset, but if you want to reach readers, you’ve got to think like a publisher.”

c) Marketing and Publicity:

This is where Nick’s creativity truly came into its own. He filmed a dystopian video ad using friends, an actor dressed as a future Boris Johnson, and even a fake Downing Street set, all to generate buzz.

“I spent a few hundred pounds on Facebook and Instagram ads, it started to tick over. For every pound I spent, I got one back in sales. But it was a grind.”

d) Reviews and Endorsements:

He secured endorsements from authors and promoted the book as part of a wider conversation about AI, politics, and identity.

“I got some great reviews, and even interest from an agent. But COVID hit. And suddenly no one wanted to read dystopian fiction anymore.”

Despite the setbacks, the process gave Nick a vital sense of creative ownership:

“You learn so much. And you get a product you can hold in your hand. But unless you have a platform already, finding readers is really tough.”

2. Publishing Can Be an Act of Liberation, but Also of Disguise

One of our most powerful and troubling conversations emerged when a participant described how she publishes widely used teaching materials — workbooks, lesson slides, and revision guides — on platforms like TES and Amazon, all under a pseudonym. Her work is regularly praised by colleagues, downloaded thousands of times, and used in classrooms across the country. But no one knows she wrote it.

“I don’t use my real name. I let them assume I’m of European descent, because when they know who I am, they treat me differently.”

She explained how her chosen name is deliberately ambiguous: male, white-sounding, unthreatening. In some of the very schools that use her materials, she feels routinely overlooked, undervalued, and underestimated. The irony couldn’t be starker.

At this point, the session took a powerful turn. It became a conversation about race, recognition, and what it means to be read on your own terms. What happens when your work is taken seriously only because people don’t know who you are? What does it mean to gain authority through disguise?

As I reflected during the session, “There’s something profoundly disturbing about being praised for your work while your identity is erased.”

And yet, her story is also one of remarkable agency. She continues to reach and help students, and to do so on her own terms. In this case, publishing becomes both a mask and a microphone: a way to be heard when you’re not allowed to be seen.

3. Getting an Agent Is Just the Beginning

Nick eventually found an agent, but only after sending out over 100 submissions. The process was, in his words, “slow, lonely, and often demoralising.” Most agents didn’t reply. A handful responded with polite rejections. Many simply disappeared into silence.

““If you’re not feeling confident when you start,” Nick said, “don’t worry, you’ll probably feel worse before it gets better. But that’s normal.”

And yet, persistence paid off. Eventually, an agent responded positively, months after the initial submission, and asked to read more. That relationship has since become a cornerstone of Nick’s current writing life.

“My agent used to be an editor, so we now collaborate closely. He gives really constructive feedback; it’s made me a better writer.”

This, perhaps, is one of the most valuable takeaways for writers at any stage: getting an agent is not a ‘golden ticket’, but it can be the start of a rich, creative partnership. Agents today, especially those with editorial experience, often work alongside authors to shape the manuscript before it even reaches a publisher.

It also highlights a deeper truth about writing and resilience. You can be talented, prepared, and deeply motivated, and still face an uphill climb. What matters is what you learn from the climb. As Nick’s experience reminds us, even in a bruising system, meaningful collaboration can emerge; if you’re lucky, and if you keep going.

4. Publishing as Pedagogy: Writing as Testimony, Writing as Teaching

Publishing is not just about markets, platforms, and metadata. It’s about meaning, about making a claim to existence, to value, to voice. This truth came home to us during a powerful free-writing exercise in the session. One participant, reflecting on her long struggle with institutional prejudice, read aloud a haunting litany of injustices she had endured as a Black student, writer, and teacher:

“Why are your biases permitted to limit me? Why can’t I create my own world and take control of my work? I am in control when I publish, but behind the veil of identity.”

This was more than reflection, it was testimony. And in that moment, it became clear that for many writers, especially those from marginalised backgrounds, publishing is not just a means of communication. It is an act of resistance. A way to exist on the page in a world that often seeks to render you invisible.

Nick picked up on this, observing how writing and publishing, even in their most modest, self-directed forms, can be acts of self-construction:

“The act of making the work, of sharing it — even with just a few readers — is a way of testifying. Of saying: I was here. I saw this.”

In this light, publishing becomes pedagogical in the deepest sense: it teaches the writer who they are becoming, and it teaches the reader to witness that becoming. This is the pedagogy of presence, of writing as a way to know and be known, even when the world says otherwise.

5. Small Presses Are Doing Vital Work, But Still Rely on Grassroots Networks

Nick now works with Inkandescent, a micro-press founded by two queer creatives determined to platform underrepresented voices, particularly those marginalised by class, race, sexuality, and geography. Their anthology, Mainstream, brought together a vibrant mix of writers whose work rarely sees the light of day in mainstream publishing. It was, against the odds, a success. Not because it had a big budget or corporate PR machine behind it, but because it was rooted in community, connection, and care.

“It’s just two guys in a bedroom, basically,” Nick told us. “But they’re doing what big publishers won’t. It’s all built on relationships.”

That phrase deserves attention. The traditional publishing industry, despite public commitments to diversity, often remains risk-averse and market-driven. Independent presses like Inkandescent, by contrast, take the long view. They work slowly. They know their writers. They often lose money. But they publish stories that matter.

Inkandescent are now considering his next book. For him, the shift from DIY self-publishing to being nurtured by a small, values-driven press has been a revelation:

“It’s not about profit. It’s about passion. They want to nurture stories, not just sell units.”

But small presses, as we discussed, are not magical solutions. They rely on mutual support, word of mouth, community events, and volunteer labour. They are fragile ecosystems, powered by networks rather than algorithms. And in many ways, they model a more mindful publishing culture: slower, more intentional, more human.

For writers, especially those at the margins, small presses offer more than opportunity. They offer solidarity. A reminder that publishing, at its best, isn’t just an industry, it’s a community of meaning-makers.

6. Publishing Trends Are Fickle. Write What You Must Write.

One of the most sobering insights Nick shared came from his experience trying to sell his latest novel, a queer coming-of-age story that had been painstakingly revised and warmly received by peers and early readers. Despite its quality, his agent was told by editors that the market was “already saturated.”

“There are already too many books like that,” one editor said, as if the existence of other queer stories somehow cancelled out the need for his.

It was a painful moment. But not an unfamiliar one for many writers. The work was good. The writing was strong. The story mattered. But it wasn’t deemed “timely,” “fresh,” or “marketable” enough by industry standards.

And yet, Nick’s response was as clear-eyed as it was defiant:

“You have to write the story that only you can tell. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

This didn’t sound like just advice; it felt like something he’d really had to live through. A reminder that the literary marketplace, shaped by trends and sales forecasts, cannot be the final arbiter of creative worth. What matters is the inner imperative, the story that insists on being written, whether or not it ever finds a publisher.

His final words to us felt like a benediction, spoken with quiet force:

“Don’t let the industry define your worth. Be your own reader. Be your own publisher, if you need to be. But above all; keep writing.”

And that is perhaps the truest lesson of all. In a world where visibility often depends on metrics, where success can feel arbitrary or elusive, the most radical act is to write anyway. To persist. To believe that your story is worth telling, not because it sells, but because it exists.

Final Reflections: Writing as Witness, Publishing as Practice

Across all six lessons, one truth resonated: publishing is not simply about putting work “out there.” It’s a creative, political, and pedagogical act. Whether we publish anonymously, through self-publishing platforms, with grassroots presses, or in mainstream forums, we are always participating in something larger: a conversation about who gets to speak, who gets heard, and what kinds of stories are allowed to take up space.

Nick’s journey reminded us that legitimacy is not conferred by industry alone. It is cultivated in community, forged in persistence, and grounded in voice. That’s why, on the MA in Creative Writing and Education, we treat publishing not as an endpoint but as a process, one that deepens reflection, invites collaboration, and foregrounds identity.

If you’re interested in exploring how writing and teaching can inform one another, how creative work can transform classrooms and communities, and how publishing can be both liberating and mindful, you’ll find further resources, reflections, and opportunities on my website: .

Because maybe publishing well does begin with writing bravely. And maybe writing bravely just means trusting your voice, even if it feels too quiet at first.