In my chapter Using Creative Writing to Fuel Creativity, published in The Oxford Handbook of Creativity and Education (Oxford University Press, 2025), I explore how creative writing, when taught mindfully, becomes a transformative educational tool. It fosters not only expressive freedom, but deeper learning and social insight. Here are five powerful ways creative writing can fuel creativity—across all disciplines.

1. Freewriting Unlocks Flow

Flow—the immersive state of deep focus—is at the heart of creative growth. I argue that freewriting is one of the most effective ways to achieve this:

“These states are achieved when humans undertake ‘painful, risky, difficult activities that stretch the person’s capacity and involve an element of novelty and discovery’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1997)… One of the best ways to do this is by encouraging regular freewriting.” (p. 6)

Freewriting bypasses internal censors and allows new ideas to emerge organically. It encourages “automaticity”—a form of intuitive thinking that unlocks insight (Bolton 2011, 2018: Elbow 1998: Hanauer 2022).

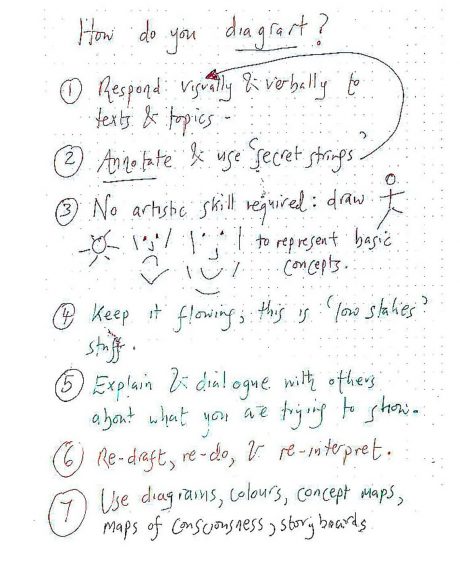

2. Diagrarting Combines Drawing, Writing, and Dialogue

To deepen the reflective process, I developed diagrarting—an original practice that fuses drawing, diagrams, and dialogue with writing:

“I coined the term ‘diagrarting’, which is the mixture of using diagrams, art and dialogue when writing/drawing creatively… not to improve people’s drawing, but to improve their writing and creative thinking.” (p. 7)

A diagrart is more than visualisation—it invites writers to talk through their work, turning the creative act into an exploratory conversation.

3. Creative Writing as Critical Literacy

Creativity flourishes when students situate their writing within the world around them—not just as isolated individuals, but as members of social, cultural, and historical contexts. As Edberg (2018) suggests, writing becomes transformative when it enables learners to engage with the world critically, recognising power structures, systemic inequality, and their own lived experience as meaningful content.

In the chapter, I advocate for creative writing as a tool for critical literacy:

“Rather than only understanding themselves as isolated individuals, [students] start to see themselves as part of a wider society… exploring how their social class, their race, their age etc has shaped who they are, what they read and what they write.” (p. 5)

This perspective aligns with decolonising pedagogy, which foregrounds voices historically marginalised by Eurocentric curricula. As Patel and Moore (2017) argue, colonisation is not just about land, but about stories—who tells them, whose are silenced, and how worldviews are shaped by economic and cultural forces. A decolonised approach to creative writing encourages learners to reclaim their narratives and to question the dominant fictions that frame education and society:

“Colonisation was… a way of seeing the world. The white, western colonisers had a narrative internalised in their heads and deeply embedded within their cultures that meant that foreign lands, other peoples and their bodies were ripe for exploitation.” (p. 4)

Through critically reflective writing practices, students can begin to dismantle these inherited narratives, explore counter-histories, and contribute to more inclusive forms of knowledge production.

4. Workshops That Heal and Empower

I critique traditional, hierarchical workshop models, arguing instead for a supportive, dialogic approach (Wenger 1999):

“For Bolton, the psychotherapist Carl Rogers’ concept of ‘unconditional positive regard’… is vital to the workshop environment: all participants are invited to read their own and other people’s work in a positive but critical light.” (p. 7)

This approach makes space for vulnerability, exploration and growth—transforming the workshop from a place of critique to one of co-creation (hooks 1994: Rogers 2004).

5. Creative Assessment for Creative Thinking

Assessment doesn’t need to stifle creativity. It can be creative too. I draw on Peter Elbow’s (1998) ideas to show how feedback can inspire rather than demoralise:

“The challenge here to teachers is to respond creatively to their pupils’ work… by making analogies for it (describing the work as weather/clothing etc), by summing up the main parts of it in a list, exploring their own experience reading it and so forth.” (p. 10)

Creative writing can be the assessment—inviting unique, responsive engagement from both student and teacher.

Whether you teach science, history, or English, creative writing offers a flexible, radical pedagogy for deeper thinking, healing, and discovery. It’s not just about telling stories—it’s about reclaiming them. You can read a Creative Commons version of the article (copyright free) here:

References

(for blog post “5 Ways Creative Writing Can Fuel Creativity” by Francis Gilbert)

- Bolton, G. (2011). Write Yourself: Creative Writing and Personal Development. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bolton, G., & Delderfield, R. (2018). Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development (5th ed.). London: SAGE.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: HarperPerennial.

- Elbow, P. (1998). Writing without Teachers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, F. (2022). “Diagrarting: Theorising and practising new ways of writing and drawing.” New Writing, 19(2), 153–182.

- Gilbert, F., & Macleroy, V. (2021). “Different ways of descending into the crypt: Methodologies and methods for researching creative writing.” New Writing, 18(3), 253–271.

- Hanauer, D.I. (2022). “The writing processes underpinning wellbeing: Insight and emotional clarity in poetic autoethnography and freewriting.” Frontiers in Communication, 7.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

- Patel, R., & Moore, J.W. (2017). A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. London: Verso.

- Rogers, C. (2004). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. London: Constable.

- Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.